Over the past 15 years, deaths from prescription opiates have quadrupled, but so has the amount of opiates prescribed. This massive increase in prescription rates has occurred while the levels of pain experienced by Americans has remain largely unchanged. Intuitively it follows that unneccessary prescriptions potentially play a significant role in the increase in opioid overdoses. An effective strategy for identifying instances of overprescribing is therefore a potentially life saving endeavor.

To that end, the goal of this experiment is to demonstrate the possibility that predictive analytics with machine learning can be used to predict the likelihood that a given doctor is a significant prescriber of opiates. I’ll do some cleaning of the data, and build a predictive model using a gradient boosted classification tree ensemble that predicts with >80% accuracy that an arbitrary entry is a significant prescriber of opioids. I’ll also do some analysis and visualization of my results combined with those pulled from other sources.

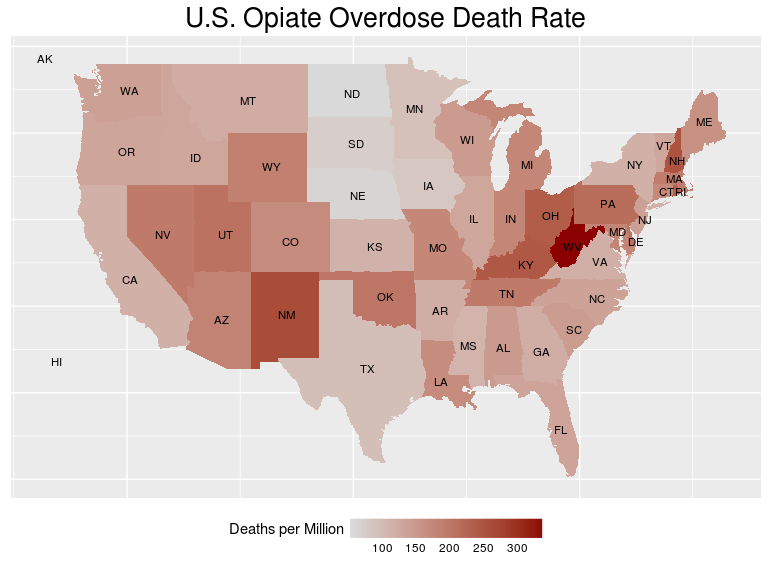

Here is a visualization of the distribution of fatal overdose rate across the country. By the end of this post, you’ll see exactly how such an image can be built.

Disclaimer I am absolutely not suggesting that doctors who prescribe opiates are culpable for overdoses. These are drugs with true medical value when used appropriately. The idea is rather that a systematic way for identifying sources may reveal trends in particular practices, fields, or regions of the country that could be used effectively to combat the problem.

Building a Dataset

The primary source of the raw data I will be pulling from is cms.org. Part of Obamacare requires more visilibity into government aid programs, so this dataset is a compilation of drug prescriptions made to citizens claiming coverage under Class D Medicare. It contains approxiately 24 million entries in .csv format. Each row contains information about one doctor and one drug, so each doctor occurs multiple times (called long format). We want to pivot this data to wide format so that each row represents a single doctor and contains information on every drug.

Those of you who have used Excel on large datasets will know very well that anything close to a million rows in Excel is painfully slow, so if you have ever wondered how to manage such a file, I’ve included the R code I used to build the dataset here.

This kind of work is pretty code-dense and not exactly riveting, so I won’t include the gory details here. Let’s just skip to the fun part. The final trimmed result is a dataset containing 25,000 unique doctors and the numbers of prescriptions written for 250 drugs in the year 2014. Specifically, The data consists of the following characteristics for each prescriber

- NPI – unique National Provider Identifier number

- Gender - (M/F)

- State - U.S. State by abbreviation

- Credentials - set of initials indicative of medical degree

- Specialty - description of type of medicinal practice

- A long list of drugs with numeric values indicating the total number of prescriptions written for the year by that individual

- Opioid.Prescriber - a boolean label indicating whether or not that individual prescribed opiate drugs more than 10 times in the year

Data Cleaning

Load the relevant libraries and read the data

library(dplyr)

library(magrittr)

library(ggplot2)

library(maps)

library(data.table)

library(lme4)

library(caret)

df <- data.frame(fread("prescriber-info.csv",nrows=-1))

First, we have to remove all of the information about opiate prescriptions from the data because that would be cheating. Conveniently, the same source that provided the raw data used to build this dataset also includes a list of all opiate drugs exactly as they are named in the data.

opioids <- read.csv("opioids.csv",skip=2)

opioids <- as.character(opioids[,2]) # second column contains the names of the opiates

opioids <- gsub("\ |-",".",opioids) # replace hyphens and spaces with periods to match the dataset

df <- df[, !names(df) %in% opioids]

Convert character columns to factors. I’m sure there is a nicer way to code this, but it’s late and this works for now. Feel free to comment the better way.

char_cols <- c("NPI",names(df)[vapply(df,is.character,TRUE)])

df[,char_cols] <- lapply(df[,char_cols],as.factor)

Now let’s clean up the factor variables

str(df[,1:5])

## 'data.frame': 25000 obs. of 5 variables:

## $ NPI : Factor w/ 25000 levels "1003002320","1003004771",..: 18016 6106 10728 16695 16924 13862 10913 10107 679 20644 ...

## $ Gender : Factor w/ 2 levels "F","M": 2 1 1 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 ...

## $ State : Factor w/ 57 levels "AA","AE","AK",..: 48 4 38 6 37 42 34 42 48 54 ...

## $ Credentials: Factor w/ 888 levels "","(DMD)","A.N.P.",..: 244 507 403 507 403 314 507 839 697 507 ...

## $ Specialty : Factor w/ 109 levels "Addiction Medicine",..: 19 29 28 42 36 29 25 63 66 42 ...

Looks like the id’s are unique and two genders is expected, but there’s a few too many states and way too many credentials.

df %>%

group_by(State) %>%

dplyr::summarise(state.counts = n()) %>%

arrange(state.counts)

## # A tibble: 57 x 2

## State state.counts

## <fctr> <int>

## 1 AA 1

## 2 AE 2

## 3 GU 2

## 4 ZZ 2

## 5 VI 3

## 6 WY 38

## 7 AK 39

## 8 VT 65

## 9 ND 66

## 10 MT 77

## # ... with 47 more rows

This site indicates that some of these are legitimate, but rare, labels Like Guam (GU), but others appear to be typos. Let’s create an “other” category for the rarely occurring abbreviations

rare.abbrev <- df %>%

group_by(State) %>%

dplyr::summarise(state.counts = n()) %>%

arrange(state.counts) %>%

filter(state.counts < 10) %>%

select(State)

# Insert a new level into the factor, then remove the old names

levels(df$State) <- c(levels(df$State),"other")

df$State[df$State %in% rare.abbrev$State] <- "other"

df$State <- droplevels(df$State)

As a quick sanity check to make sure we still don’t have any bogus states, let’s pull that table from the web and make sure our abbreviations are valid

library(htmltab)

state.abbrevs <- data.frame(htmltab("http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0110468.html",which=2))

state.abbrevs <- state.abbrevs$Postal.Code

if (all(levels(df$State)[levels(df$State)!="other"] %in% state.abbrevs)){print("All abbreviations are valid")} else{print("Uh oh..")}

Looking ahead, I’m going to be interested in the variable importance state-by-state, so instead of using a single factor I’ll convert to dummy variables so each can be scored separately.

df <- cbind(df[names(df)!="State"],dummy(df$State))

Let’s look at Credentials now

df %>%

group_by(Credentials) %>%

dplyr::summarise(credential.counts = n()) %>%

arrange(credential.counts) %>%

data.frame() %>%

head(n=25)

## Credentials credential.counts

## 1 (DMD) 1

## 2 A.P.R.N. N.P. 1

## 3 A.P.R.N., B.C. 1

## 4 A.P.R.N., W.H.N.P. 1

## 5 A.R.N.P. , PMHNP-BC 1

## 6 A.R.N.P.-B.C. 1

## 7 A.T.,C. , C.S.C.S. 1

## 8 ACNP-BC, CCNS 1

## 9 ACNP-BC, MSN 1

## 10 ACNP/FNP 1

## 11 ACNS-BC 1

## 12 ADULT NP 1

## 13 AGACNP 1

## 14 AGNP 1

## 15 AGPCNP-BC 1

## 16 AHCNS 1

## 17 ANNA TAVAKKOLI M.D. 1

## 18 ANP B-C 1

## 19 ANP-BC, GNP 1

## 20 ANP-FNP-BC 1

## 21 ANP,BC 1

## 22 ANP. 1

## 23 ANP/CNP 1

## 24 ANRP 1

## 25 APN FNP-C 1

The credentials are quite the mess. Titles are inconsistently entered with periods, spaces, hyphens, etc, and many people have multiple credentials. While it’s easy to make use of regular expressions to clean them, I won’t bother because I suspect most of the predictive information contained in Credentials will be captured by Specialty.

# 7 years of college down the drain

df %<>%

select(-Credentials)

On that note, let’s look at Specialty

df %>%

group_by(Specialty) %>%

dplyr::summarise(specialty.counts = n()) %>%

arrange(desc(specialty.counts)) %>%

data.frame() %>%

head(n=25)

## Specialty

## 1 Internal Medicine

## 2 Family Practice

## 3 Dentist

## 4 Nurse Practitioner

## 5 Physician Assistant

## 6 Emergency Medicine

## 7 Psychiatry

## 8 Cardiology

## 9 Obstetrics/Gynecology

## 10 Orthopedic Surgery

## 11 Optometry

## 12 Student in an Organized Health Care Education/Training Program

## 13 Ophthalmology

## 14 General Surgery

## 15 Gastroenterology

## 16 Neurology

## 17 Podiatry

## 18 Dermatology

## 19 Urology

## 20 Psychiatry & Neurology

## 21 Pulmonary Disease

## 22 Otolaryngology

## 23 General Practice

## 24 Nephrology

## 25 Hematology/Oncology

## specialty.counts

## 1 3194

## 2 2975

## 3 2800

## 4 2512

## 5 1839

## 6 1087

## 7 691

## 8 688

## 9 615

## 10 575

## 11 571

## 12 547

## 13 519

## 14 487

## 15 399

## 16 371

## 17 369

## 18 344

## 19 328

## 20 266

## 21 262

## 22 260

## 23 247

## 24 236

## 25 218

There’s a ton of ways to go about attacking this feature. Since there does not appear to be too much name clashing/redundancy, I’ll use a couple of keywords to collapse some specialties together, and I’ll also lump the rarely occurring ones together into an “other” category like before.

# Get the common specialties, we won't change those

common.specialties <- df %>%

group_by(Specialty) %>%

dplyr::summarise(specialty.counts = n()) %>%

arrange(desc(specialty.counts)) %>%

filter(specialty.counts > 50) %>%

select(Specialty)

common.specialties <- levels(droplevels(common.specialties$Specialty))

# Default to "other", then fill in. I'll make special levels for surgeons and collapse any category containing the word pain

new.specialties <- factor(x=rep("other",nrow(df)),levels=c(common.specialties,"Surgeon","other","Pain.Management"))

new.specialties[df$Specialty %in% common.specialties] <- df$Specialty[df$Specialty %in% common.specialties]

new.specialties[grepl("surg",df$Specialty,ignore.case=TRUE)] <- "Surgeon"

new.specialties[grepl("pain",df$Specialty,ignore.case=TRUE)] <- "Pain.Management"

new.specialties <- droplevels(new.specialties)

df$Specialty <- new.specialties

df %>%

group_by(Specialty) %>%

dplyr::summarise(specialty.counts = n()) %>%

arrange(desc(specialty.counts)) %>%

data.frame() %>%

head(n=25)

## Specialty

## 1 Internal Medicine

## 2 Family Practice

## 3 Dentist

## 4 Nurse Practitioner

## 5 Physician Assistant

## 6 Surgeon

## 7 Emergency Medicine

## 8 Psychiatry

## 9 Cardiology

## 10 Obstetrics/Gynecology

## 11 Optometry

## 12 Student in an Organized Health Care Education/Training Program

## 13 Ophthalmology

## 14 other

## 15 Gastroenterology

## 16 Neurology

## 17 Podiatry

## 18 Dermatology

## 19 Urology

## 20 Psychiatry & Neurology

## 21 Pulmonary Disease

## 22 Otolaryngology

## 23 General Practice

## 24 Nephrology

## 25 Hematology/Oncology

## specialty.counts

## 1 3194

## 2 2975

## 3 2800

## 4 2512

## 5 1839

## 6 1689

## 7 1087

## 8 691

## 9 688

## 10 615

## 11 571

## 12 547

## 13 519

## 14 454

## 15 399

## 16 371

## 17 369

## 18 344

## 19 328

## 20 266

## 21 262

## 22 260

## 23 247

## 24 236

## 25 218

Looks good. Like we did with states, let’s make it a dummy so we can score the importance by specialty.

df <- df[!is.na(df$Specialty),]

df <- cbind(df[,names(df)!="Specialty"],dummy(df$Specialty))

Because this data is a subset of a larger dataset, it is possible that there are drugs here that aren’t prescribed in any of the rows (i.e. the instances where they were prescribed got left behind). This would result in columns of all 0, which is bad. Multicollinear features are already bad because they mean the feature matrix is rank-deficient and, therefore, non-invertible. But beyond that, pure-zero features are a special kind of useless. Let’s remove them.

df <- df[vapply(df,function(x) if (is.numeric(x)){sum(x)>0}else{TRUE},FUN.VALUE=TRUE)]

I used vapply because sapply is unpredictable

Model Building

I’ll use a gradient boosted classification tree ensemble with gbm and caret. My reasoning is that with so many different features in the form of individual drugs, it’s extremely likely that some of them are highly correlated (i.e. high blood pressure, heart medication, Aspirin). Something like an L1 regularized logistic regression followed by feature trimming would also work, but one of the nice things about this type of tree model is that it doesn’t care about multicollinear features.

First, split the data.

train_faction <- 0.8

train_ind <- sample(nrow(df),round(train_faction*nrow(df)))

Remove the non-features, and convert the target label to something non-numeric (this package requires that)

df %<>% select(-NPI)

df$Opioid.Prescriber <- as.factor(ifelse(df$Opioid.Prescriber==1,"yes","no"))

train_set <- df[train_ind,]

test_set <- df[-train_ind,]

Now we build the model. I’ll use a 5-fold cross validation to optimize hyperparameters for the boosted tree ensemble. A downside of trees is they take a while to train (though they predict quickly). A production model would call for an exhaustive hyperparameter search, but to keep the running time of this script reasonable I will search only a few parameters. I’ll run this and go grab some coffee.

objControl <- trainControl(method='cv', number=5, returnResamp='none', summaryFunction = twoClassSummary, classProbs = TRUE, verboseIter = TRUE,savePredictions = TRUE)

model <- train(train_set %>% select(-Opioid.Prescriber),train_set$Opioid.Prescriber,

method='gbm',

metric = "ROC",

# metric = "Accuracy",

trControl=objControl,

tuneGrid=data.frame(n.trees=c(50,150,200),

interaction.depth=c(3),

shrinkage=c(0.1),

n.minobsinnode=c(10)))

## + Fold1: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## Iter TrainDeviance ValidDeviance StepSize Improve

## 1 1.2427 nan 0.1000 0.0567

## 2 1.1495 nan 0.1000 0.0466

## 3 1.0717 nan 0.1000 0.0389

## 4 1.0058 nan 0.1000 0.0325

## 5 0.9489 nan 0.1000 0.0286

## 6 0.9012 nan 0.1000 0.0237

## 7 0.8592 nan 0.1000 0.0208

## 8 0.8234 nan 0.1000 0.0178

## 9 0.7920 nan 0.1000 0.0153

## 10 0.7646 nan 0.1000 0.0135

## 20 0.6128 nan 0.1000 0.0043

## 40 0.5327 nan 0.1000 0.0006

## 60 0.5071 nan 0.1000 0.0004

## 80 0.4907 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 100 0.4782 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 120 0.4669 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 140 0.4599 nan 0.1000 0.0000

## 160 0.4522 nan 0.1000 -0.0000

## 180 0.4468 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 200 0.4405 nan 0.1000 0.0000

##

## - Fold1: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## + Fold2: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## Iter TrainDeviance ValidDeviance StepSize Improve

## 1 1.2442 nan 0.1000 0.0565

## 2 1.1520 nan 0.1000 0.0463

## 3 1.0744 nan 0.1000 0.0388

## 4 1.0093 nan 0.1000 0.0326

## 5 0.9533 nan 0.1000 0.0277

## 6 0.9053 nan 0.1000 0.0238

## 7 0.8644 nan 0.1000 0.0205

## 8 0.8286 nan 0.1000 0.0177

## 9 0.7982 nan 0.1000 0.0153

## 10 0.7712 nan 0.1000 0.0134

## 20 0.6192 nan 0.1000 0.0042

## 40 0.5393 nan 0.1000 0.0008

## 60 0.5099 nan 0.1000 0.0009

## 80 0.4908 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 100 0.4802 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 120 0.4713 nan 0.1000 0.0000

## 140 0.4638 nan 0.1000 -0.0001

## 160 0.4576 nan 0.1000 -0.0001

## 180 0.4516 nan 0.1000 -0.0001

## 200 0.4456 nan 0.1000 0.0001

##

## - Fold2: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## + Fold3: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## Iter TrainDeviance ValidDeviance StepSize Improve

## 1 1.2441 nan 0.1000 0.0561

## 2 1.1515 nan 0.1000 0.0464

## 3 1.0738 nan 0.1000 0.0384

## 4 1.0080 nan 0.1000 0.0329

## 5 0.9531 nan 0.1000 0.0275

## 6 0.9056 nan 0.1000 0.0237

## 7 0.8646 nan 0.1000 0.0205

## 8 0.8287 nan 0.1000 0.0180

## 9 0.7984 nan 0.1000 0.0154

## 10 0.7710 nan 0.1000 0.0136

## 20 0.6187 nan 0.1000 0.0042

## 40 0.5380 nan 0.1000 0.0007

## 60 0.5118 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 80 0.4944 nan 0.1000 0.0005

## 100 0.4827 nan 0.1000 -0.0001

## 120 0.4743 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 140 0.4669 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 160 0.4591 nan 0.1000 0.0000

## 180 0.4531 nan 0.1000 0.0000

## 200 0.4479 nan 0.1000 -0.0000

##

## - Fold3: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## + Fold4: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## Iter TrainDeviance ValidDeviance StepSize Improve

## 1 1.2433 nan 0.1000 0.0568

## 2 1.1511 nan 0.1000 0.0461

## 3 1.0727 nan 0.1000 0.0391

## 4 1.0061 nan 0.1000 0.0325

## 5 0.9514 nan 0.1000 0.0275

## 6 0.9034 nan 0.1000 0.0237

## 7 0.8619 nan 0.1000 0.0206

## 8 0.8264 nan 0.1000 0.0175

## 9 0.7958 nan 0.1000 0.0152

## 10 0.7688 nan 0.1000 0.0133

## 20 0.6168 nan 0.1000 0.0045

## 40 0.5383 nan 0.1000 0.0005

## 60 0.5088 nan 0.1000 0.0005

## 80 0.4929 nan 0.1000 0.0004

## 100 0.4806 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 120 0.4699 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 140 0.4625 nan 0.1000 0.0000

## 160 0.4549 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 180 0.4503 nan 0.1000 -0.0000

## 200 0.4453 nan 0.1000 -0.0000

##

## - Fold4: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## + Fold5: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## Iter TrainDeviance ValidDeviance StepSize Improve

## 1 1.2440 nan 0.1000 0.0569

## 2 1.1507 nan 0.1000 0.0465

## 3 1.0730 nan 0.1000 0.0388

## 4 1.0067 nan 0.1000 0.0328

## 5 0.9509 nan 0.1000 0.0276

## 6 0.9030 nan 0.1000 0.0239

## 7 0.8618 nan 0.1000 0.0207

## 8 0.8257 nan 0.1000 0.0179

## 9 0.7948 nan 0.1000 0.0153

## 10 0.7672 nan 0.1000 0.0136

## 20 0.6146 nan 0.1000 0.0044

## 40 0.5379 nan 0.1000 0.0014

## 60 0.5094 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 80 0.4923 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 100 0.4804 nan 0.1000 -0.0000

## 120 0.4720 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 140 0.4640 nan 0.1000 -0.0001

## 160 0.4581 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 180 0.4512 nan 0.1000 0.0000

## 200 0.4462 nan 0.1000 -0.0000

##

## - Fold5: shrinkage=0.1, interaction.depth=3, n.minobsinnode=10, n.trees=200

## Aggregating results

## Selecting tuning parameters

## Fitting n.trees = 200, interaction.depth = 3, shrinkage = 0.1, n.minobsinnode = 10 on full training set

## Iter TrainDeviance ValidDeviance StepSize Improve

## 1 1.2444 nan 0.1000 0.0567

## 2 1.1511 nan 0.1000 0.0464

## 3 1.0737 nan 0.1000 0.0387

## 4 1.0077 nan 0.1000 0.0327

## 5 0.9520 nan 0.1000 0.0276

## 6 0.9038 nan 0.1000 0.0237

## 7 0.8630 nan 0.1000 0.0206

## 8 0.8273 nan 0.1000 0.0176

## 9 0.7966 nan 0.1000 0.0153

## 10 0.7689 nan 0.1000 0.0137

## 20 0.6179 nan 0.1000 0.0042

## 40 0.5393 nan 0.1000 0.0017

## 60 0.5108 nan 0.1000 0.0003

## 80 0.4923 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 100 0.4826 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 120 0.4728 nan 0.1000 0.0000

## 140 0.4656 nan 0.1000 0.0000

## 160 0.4589 nan 0.1000 0.0001

## 180 0.4533 nan 0.1000 0.0002

## 200 0.4494 nan 0.1000 -0.0000

predictions <- predict(model,test_set%>% select(-Opioid.Prescriber),type="raw")

confusionMatrix(predictions,test_set$Opioid.Prescriber,positive="yes")

## Confusion Matrix and Statistics

##

## Reference

## Prediction no yes

## no 1951 417

## yes 70 2562

##

## Accuracy : 0.9026

## 95% CI : (0.894, 0.9107)

## No Information Rate : 0.5958

## P-Value [Acc > NIR] : < 2.2e-16

##

## Kappa : 0.8032

## Mcnemar's Test P-Value : < 2.2e-16

##

## Sensitivity : 0.8600

## Specificity : 0.9654

## Pos Pred Value : 0.9734

## Neg Pred Value : 0.8239

## Prevalence : 0.5958

## Detection Rate : 0.5124

## Detection Prevalence : 0.5264

## Balanced Accuracy : 0.9127

##

## 'Positive' Class : yes

##

Looks like we did a good job, the accuracy is not bad for a first attempt. If our goal is to predict significant sources of opioid prescriptions for the purpose of some government agency doing investigative work, then we would likely care more about precision (Pos Pred Value in this package) than accuracy. The reason is because a false positive is potentially sending people on a wild goose chase, wasting money and time.

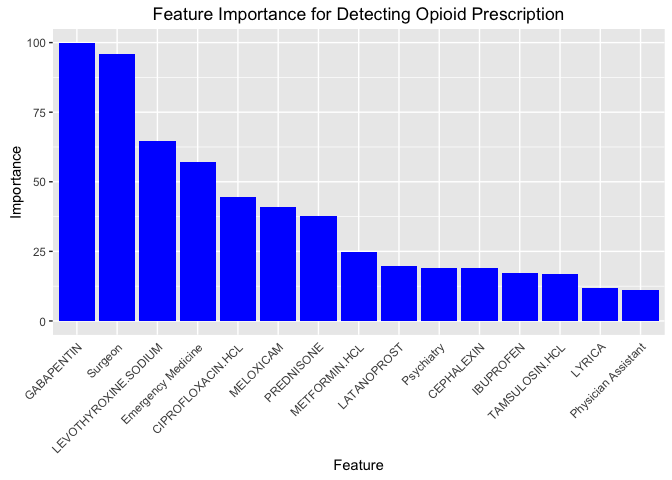

The other nice thing about trees is the ability to view the importance of the features in the decision making process. This is done by cycling through each feature, randomly shuffling its values about, and seeing how much that hurts your cross-validation results. If shuffling a feature screws you up, then it must be pretty important. Let’s extract the importance from our model with varImp and make a bar plot.

importance <- as.data.frame(varImp(model)[1])

importance <- cbind(row.names(importance), Importance=importance)

row.names(importance) <-NULL

names(importance) <- c("Feature","Importance")

importance %>% arrange(desc(Importance)) %>%

mutate(Feature=factor(Feature,levels=as.character(Feature))) %>%

slice(1:15) %>%

ggplot() + geom_bar(aes(x=Feature,y=(Importance)),stat="identity",fill="blue") +

theme(axis.text.x=element_text(angle=45,vjust = 1,hjust=1),axis.ticks.x = element_blank()) +ylab("Importance") +ggtitle("Feature Importance for Detecting Opioid Prescription")

Our best feature was a drug called Gabapentin, which unsurprisingly is used to treat nerve pain caused by things like shingles. It’s not an opiate, but likely gets prescribed at the same time. The Surgeon feature we engineered has done quite well. The other drugs are for various conditions including inflamatation, cancer, and athritis among others.

It probably doesn’t surprise anybody that surgeons commonly prescribe pain medication, or that the people taking cancer drugs are also taking pain pills. But with a very large feature set it becomes entirely intractable for a human to make maximal use of the available information. I would expect a human analyzing this data would immediately classify candidates based upon their profession, but machine learning has enabled us to break it down further based upon the specific drug prescription trends doctor by doctor. Truly a powerful tool.

Summary/Analysis

We succeeded in building a pretty good opiate-prescription detection algorithm based primarily on their profession and prescription rates of non-opiate drugs. This could be used to combat overdoses in a number of ways. Professions who show up with high importance in the model can reveal medical fields that could benefit in the long run from curriculum shifts towards awareness of the potential dangers. Science evolves rapidly, and this sort of dynamic shift of the “state-of-the-art” opinion is quite common. It’s also possible that individual drugs that are strong detectors may identify more accurately a sub-specialty of individual prescribers that could be of interest, or even reveal hidden avenues of illegitimate drug access.

Now, as promised, here is the code used to generate the figure at the beginning of the post.

all_states <- map_data("state")

od <- read.csv("overdoses.csv",stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

od$State <- as.factor(od$State)

od$Population <- as.numeric(gsub(",","",od$Population))

od$Deaths <- as.numeric(gsub(",","",od$Deaths))

od %>%

mutate(state.lower=tolower(State), Population=as.numeric(Population)) %>%

merge(all_states,by.x="state.lower",by.y="region") %>%

select(-subregion,-order) %>%

ggplot() + geom_map(map=all_states, aes(x=long, y=lat, map_id=state.lower,fill=Deaths/Population*1e6) ) + ggtitle("U.S. Opiate Overdose Death Rate") +

geom_text(data=data.frame(state.center,od$Abbrev),aes(x=x, y=y,label=od.Abbrev),size=3) +

scale_fill_continuous(low='gray85', high='darkred',guide=guide_colorbar(ticks=FALSE,barheight=1,barwidth=10,title.vjust=.8,values=c(0.2,0.3)),name="Deaths per Million") + theme(axis.text=element_blank(),axis.title=element_blank(),axis.ticks=element_blank(),legend.position="bottom",plot.title=element_text(size=20))

As you can see, it’s a serious problem. Maybe we as data scientists have the tools to make a difference.